By Polina Kempinsky

Guest Contributor

The terror attack on Oct. 7 has shaken my worldview to the core. I stopped feeling safe, became fearful, and started to wonder where I belong. To strengthen the sentiment, there was an increase in tension and antisemitism at Harvard University.

It’s important to say that, for the most part, the support I received from many friends and professors, from the first day, was incredible. Many, including members of the Muslim community, have reached out. I felt like I was receiving an incredible hug from them, as well as from the local Jewish community, without which I couldn’t have made it.

But there were other voices as well. Some have started as early as Oct. 7; others have become louder over time. The key question, at least for me, is not whether Harvard University president Claudine Gay should resign or not. The question is what can be done to address antisemitism’s core drivers on campus—stemming from the community and the institutions.

What drives the issue?

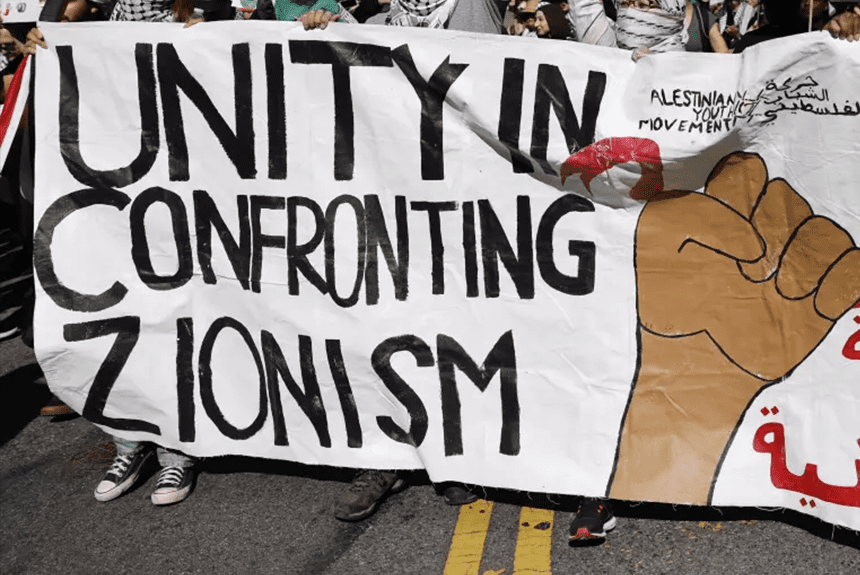

As to the community, much of the discourse is aggressive—or occurring in an echo chamber—sometimes turning into violence. For example, much of Harvard’s internal communication is occurring on Sidechat, an anonymous community-based app, featuring almost daily antisemitic posts. Israelis in school WhatsApp groups are often receiving aggressive and antisemitic comments. There was at least one documented incident of a physical attack of a Jew on campus.

As an institution, it feels like we’re alone in this. Some relevant university officials attempt avoiding conversations with us. At the end of the day, even if officials have attended meetings with us, as the president mentioned in the hearing, the outcome is still not there. Events of aggression toward Jews are often overlooked or belittled. For example, imagine getting out of class to a chanting of “from the river to the sea”—and seeing a senior university official standing next to you, knowing that you’re Jewish, and not saying anything. At the end of the day, Jewish (as well as Muslim) students don’t feel safe on campus, and the university’s response to it, if even happening, is often too little, too late.

Looking for solutions

There are no simple solutions to these issues. I understand, respect, and cherish the right of people to free speech, but I often struggle to understand why my right to feel safe is secondary.

If I could express three wishes, I’d ask for protocols, space for bottom-up initiatives and creation of a culture of discussion.

As for protocols, I want clear guidelines as to the university’s responsibility when handling antisemitic or Islamophobic occurrences: point of contact, timelines, guidelines, and methods. I would want a clear mechanism to know that I get the protection I need, when I need it—regardless of context, in a similar manner to best practice ombudsman positions.

As for space for bottom-up initiatives, the logic stems from the university’s long time to react. It took the university over two weeks to offer “community spaces” after Oct. 7 for impacted students. Students have managed to create such spaces for themselves within hours. A month after Oct. 7, I led an initiative of small group discussions on the topic, bringing together students from across the political spectrum to openly talk about the situation—an initiative that has created collaborations and built bridges between communities. The university has been promising such a space since Oct. 7, and as of now, I have attended one such teach-in as late as December. I’m not saying this failure stems from ill intentions, as much as this is the nature of things, like markets determining prices or the benefits of democracy.

The third is creating a culture of discussion, which is in the hands of faculty. In one of my classes this semester, after receiving comments on not creating an engaging enough space, the professor asked us to debate on several topics. One of them was “for/against Black face.” As a student rightfully responded, this is as useful as debating for/against clean water. There are so many other topics that could be discussed—why are we not using them? We’re not used to having difficult or complex conversations at school, often because we’re told we don’t have to. But if we can’t do it at Harvard, where and when will we be able to do so?

Polina Kempinsky, 27, is a master’s in public policy student at The Harvard Kennedy School. She is from Israel and previously worked as a consultant at Boston Consulting Group. She holds a BA in philosophy, politics and economics from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.