By Kara Baskin

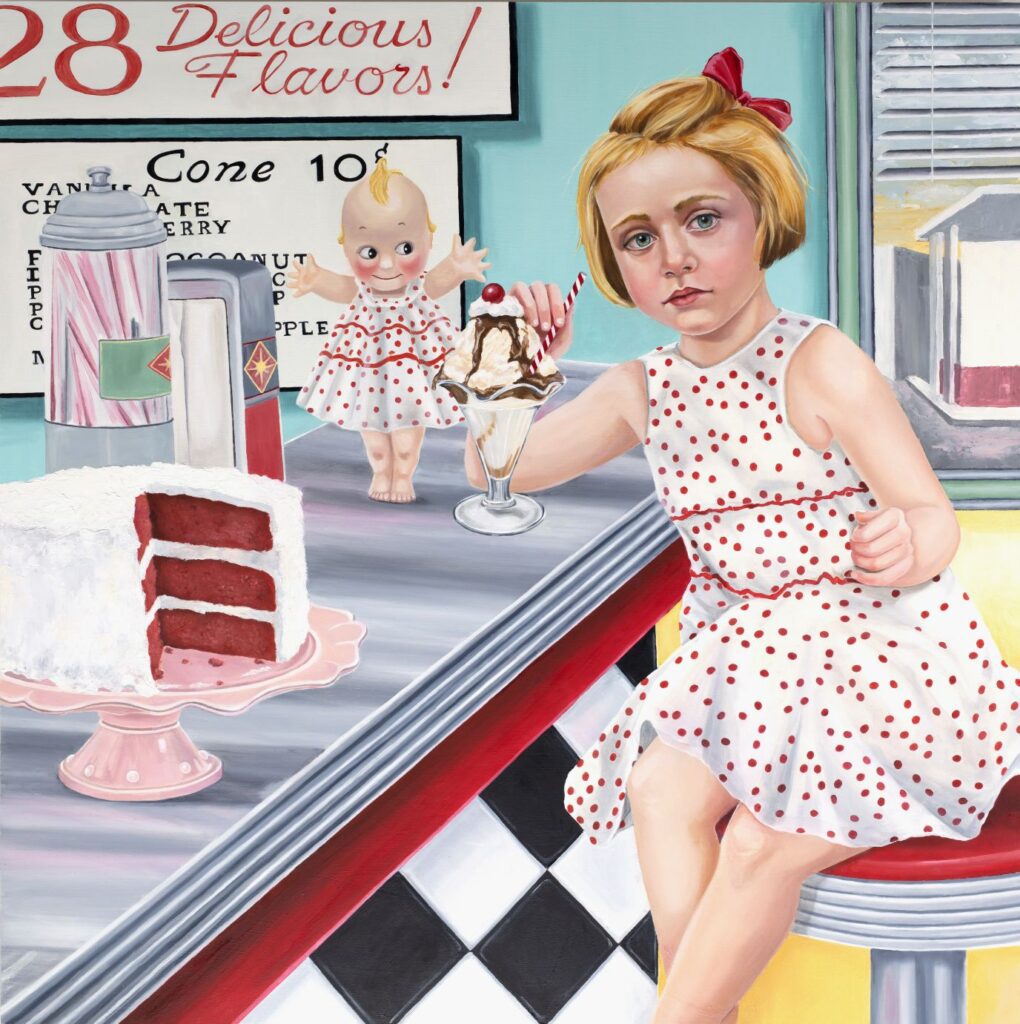

Starting on Sept. 7, 2023, the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute at Brandeis University welcomes a revolutionary multimedia exhibition spotlighting the Holocaust’s youngest victims. “Lives Eliminated, Dreams Illuminated” (LEDI) memorializes 23 young women and girls who were murdered during the Holocaust with paintings based on archival photographs, accompanied by unique musical compositions and narrative storytelling.

Rina, Anna, Marcelle, Eva and more: Their short lives are captured in soul-stirring portraits by renowned American painter Lauren Bergman and accompanied by music from award-winning Israeli composer Ella Milch-Sheriff, the child of Holocaust survivors. Both artists specialize in the frailty of human life and the complexity of human emotion, especially as it relates to women.

Unlike many museum exhibits, this one is wholly interactive and immersive; each visitor is given headphones to experience each piece of art and vignette as a stand-alone piece, ideally spending five minutes or so per painting, composition and corresponding original photograph. There’s time to pause and contemplate; time to absorb; time to connect not just intellectually but emotionally with each work, visually and musically.

Milch-Sheriff’s cousin, arts and social impact philanthropist Dr. David Milch, conceived of the LEDI experience during a chance meeting with Bergman in 2019 at New York City’s Pierre Hotel. Also the son of Holocaust survivors, Milch was attending an event to support the Museum of Eternal Faith and Resilience. Bergman’s Holocaust portraits and stark captions were on display—and he was moved by her ability to crystallize the brevity of these lost lives through the dichotomy of archival photos and artistic reinterpretations of their faces.

“I found myself in front of a beautiful painting of [Holocaust victim] Eva Nemova. I looked at a photograph next to the painting, read the caption and froze: I immediately realized that I was looking at an archival photograph of a young girl who had been murdered in the Holocaust and that this was her life reimagined in the portrait. I was struck by it,” Milch recalls.

Not long after, he introduced Bergman to his prolific composer cousin, Milch-Sheriff, at a separate event. The two hit it off, and they began to imagine the portraits set to musical vignettes.

“Music goes directly to certain senses that are not necessarily our intellect [or emotions]. It speaks directly to our wholeness,” says Milch-Sheriff, who composed many of the haunting pieces from her small apartment in Tel Aviv, Israel, during the early days of COVID-19.

“When I listened to Ella’s music, I could feel the paintings in a completely different way. It makes it like 3D—all-surrounding,” Bergman says.

Bergman originally began the portraits in 2017, in response to the Unite the Right white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, an eerie echoing of the Nazi rallies in the 1930s. Milch-Sheriff’s compositions gave her work a new dimension, thanks to the duo’s rapport.

“When I first met Ella, we just went off by ourselves, chatting. I didn’t know about her. She didn’t know anything about me. But we just started talking, and I immediately sensed that we had a very deep connection. There’s this spark of ‘aha!’ when you meet someone who inspires you and who’s in sync with your message and your goals,” Bergman says.

Bergman’s message comes from a place of despair—but hope, too.

“This is a call to stand up against the hatred and divisiveness that’s rising around us,” Bergman says. “The call to action is to not be a bystander.”

After Charlottesville, and amid news of children being ripped from their parents’ arms at the U.S. border, she began to worry about the country’s new trajectory, “away from the tolerance and inclusivity I thought we were moving toward … and it shattered me. I had never, ever anticipated that I would see neo-Nazis and white supremacists marching through the streets,” she says.

Now, Bergman hopes that LEDI reminds visitors how fragile democracy truly is, and how women in particular are uniquely vulnerable, especially in a world where their rights are being stripped away in various settings.

“My work is always about describing societal issues through the female lens,” she says. “My mother was both a model and a feminist activist, so there was this juxtaposition of the idealized female, the beauty, with an activist, strong woman. My work has always probed those issues: What does it mean to be a female in society with these contradictory messages?”

Milch thinks back to 9/11, and how quickly the twin towers—and so many lives—were exterminated. He recalls how long it took to rebuild, and how hatred can reverberate for years, decades and centuries. Progress takes time; destruction happens immediately.

“Disorder happens furiously fast, whereas something creative takes time and intentionality,” he says. “My hope is that an exhibition like this stops people for a moment and focuses them on something which, truly, in my mother’s living memory, happened out of seemingly nowhere and had a reverberating effect with the escalation of antisemitism and intolerance.”

Indeed, there’s another family connection: Milch’s mom, 92-year-old Lusia Rosenzweig Milch, is also featured in the exhibition. She lost more than 100 family members in the Holocaust. She crossed the German Alps in mid-winter to safety in Italy, arriving in New York City, where she still lives today. In the exhibit, she shares personal memories and stories along with her portrait, adding one more humanistic element to an exhibit that manages to capture the most inhumane of horrors.

“Art and artistry give us a window, a mirror, a lever into understanding these tragedies of history. How do you deal with 6 million people killed during the Holocaust? One-and-a-half-million children. The numbers just numb us. But, if you can connect to an individual child via art and artistry, if it makes an emotional connection? We know how the brain works. The brain connects to things emotionally, and you can’t forget it,” Milch says.

Learn more about the exhibit, which will be at Brandeis University in Waltham from Sept. 7 through Oct. 25, 2023, at livesdreams.com.

Kara Baskin is the parenting writer for JewishBoston.com. She is also a regular contributor to The Boston Globe and a contributing editor at Boston Magazine. She has worked for New York Magazine and The New Republic, and helped to launch the now-defunct Jewish Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Email her at kara@jewishboston.com.