By Mimi Lemay

“What can I say?” my mother would shrug, on the occasions that I would let down my guard and empathize with the fact that my life choices had made hers more complicated: “What can I say? I have a foot in two worlds. I love them both.”

Sometimes these ruminations would conclude with a query to the Almighty: “I don’t know why Hashem (God) has asked this of me, and sometimes I ask Him, ‘Why?’ But, this is my reality. I have a foot in two worlds.”

The two worlds to which my mother referred were not demarcated by the 3,000 odd miles from the house she shared with my stepfather in Gateshead, England, and my home with her three grandchildren in small-town Massachusetts. The far wider gulf was the one between her world of stringent Torah observance and values, and my world, secular or frei (free) of these rituals and regulations.

In crossing the chasm for each visit to our home, she emerged from the plane a striking figure in her long, dark skirts, buttoned-up shirts and a wig or kerchief covering her hair, even in the sweltering heat of summer. Her kosher cookware and dishes rose from their boxes in our basement and, for the next few weeks, replaced our “treif” items, her aromatic cooking bringing in the neighbors, who loved her. Her Hebrew and religious texts sat astride our secular volumes. Two worlds, two very different lives and one diminutive woman stepping back and forth, in apparent disregard for the inviolable lines.

The crossing was far from seamless. At times we tussled, hurling recriminations at each other: I was accused of rejecting her world; she was accused of imposing hers on mine. It is only with age and maturity that I have come to appreciate how rare an act of love it was for her to cross this divide as wholeheartedly as she did, not only making peace with my secular existence, but expressing support for first one, then another of our family who came out as LGBTQ+.

The world to which she returned at the end of each visit made no bones in its rejection of Jews who dared to love someone of the same sex, or try to live authentically as the gender they knew themselves to be. My mother, however, had managed to boil down the circumstances in which she found herself to these essentials: God gave her these two worlds, and therefore she must find a way to live in both.

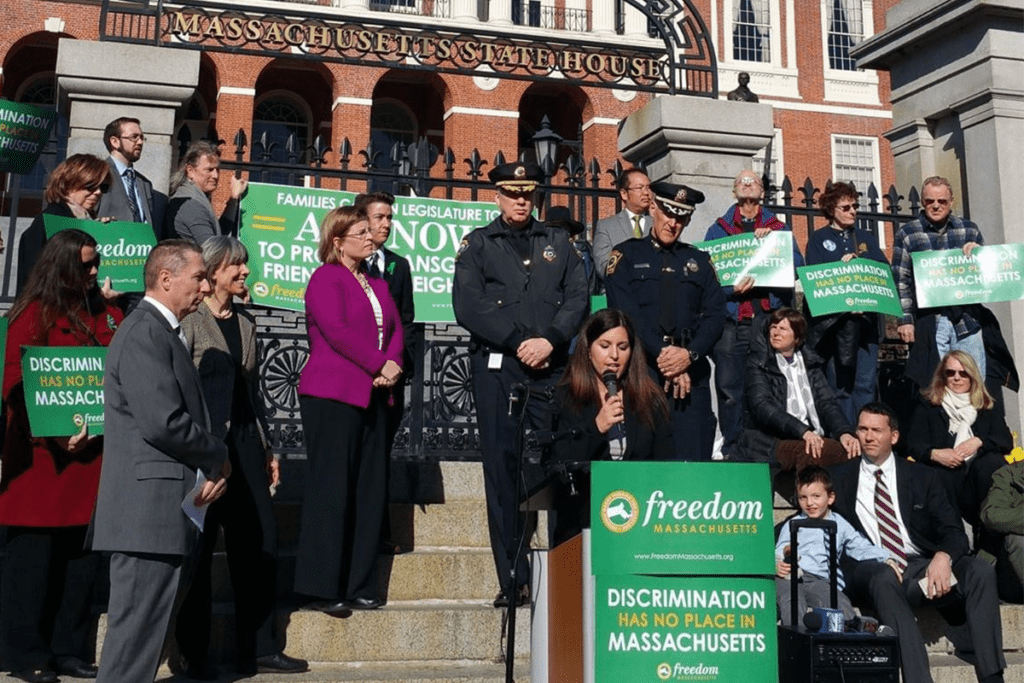

My own world-straddling endeavors began nearly a decade ago, though at the time, I was unaware of occupying a liminal space. Realizing the lack of secure rights afforded to the LGBTQ+ community and the horrific discrimination to which they were subjected, I began my work as an advocate, writing and speaking in support of important equality legislation, walking the halls of our State House, even appearing occasionally on television. My focus soon widened to the national movement for LGBTQ+ rights, and I began to devote my time and efforts at larger, national civil rights organizations, linking hands with many of this country’s well-known activists.

In the earliest years of my advocacy, I rarely brought up my Jewish heritage, something that still prompted complicated feelings in me, given the ultra-Orthodox upbringing that I had rejected. Instead, I steered conversations toward universally relatable themes: the desire to have my children grow up in a world where one’s authentic self was accepted, free of harmful and often violent bias.

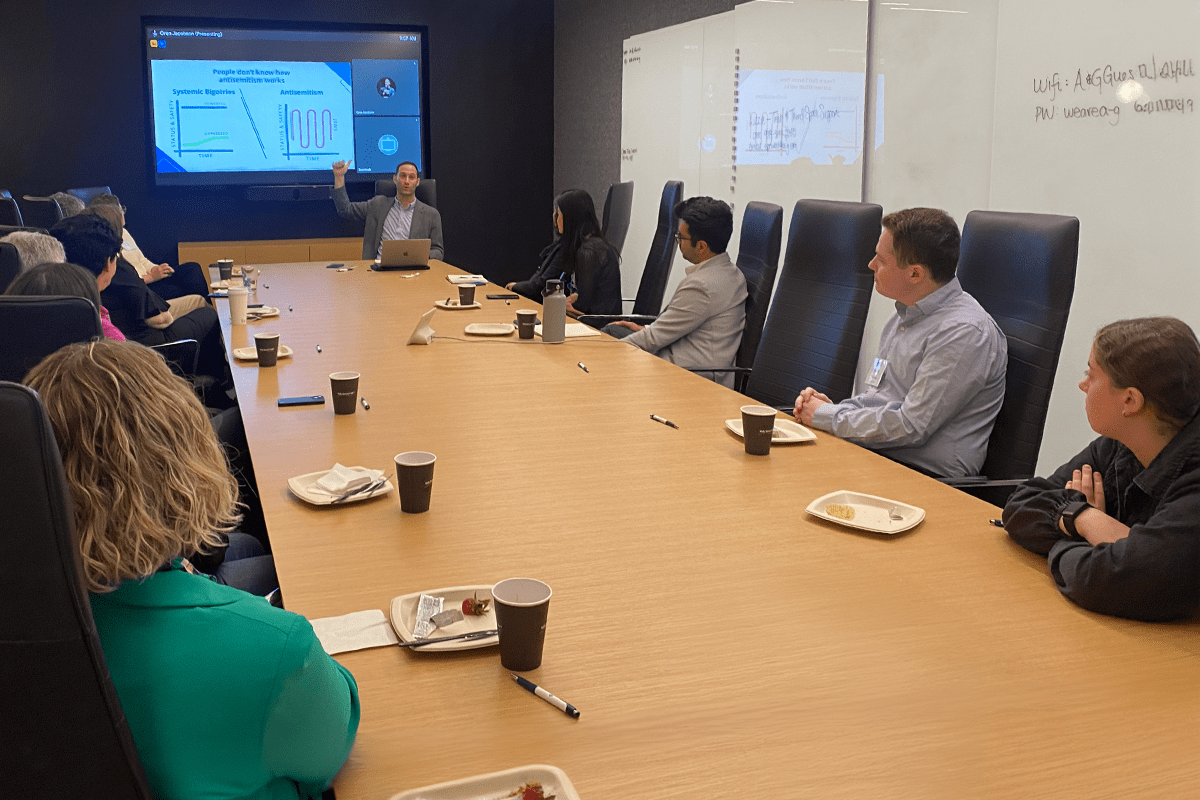

As I matured in my advocacy, I learned to be deliberately intersectional in my approach. “Intersectionality” meant accounting for the fact that individuals holding more than one marginalized identity often experienced the compounding effect of multiple discriminations and, therefore, lived in greater vulnerability. Accounting for intersectionality yielded several benefits. Considering factors other than LGBTQ+ status in our work enabled us to hone in on the specific needs of different communities. It also enabled triaging. Those who experienced the greatest multiplicity of vulnerabilities would require the most immediate effort and attention. Finally, it encouraged coalition-building with other social justice movements, expanding our reach and harnessing the power of intercommunal action. We were, inarguably, stronger together.

I myself began to “lean in” to my Jewish identity as an advocate, realizing that my own personal journey as a formerly ultra-Orthodox woman, far from being irrelevant to my work, was a helpful tool for modeling how understanding about gender and sexuality can evolve. During my hours speaking and writing about my previous Jewish identity, I found myself, to my surprise, in the process of creating a new one, distinct from the one I had discarded in my early 20s. I discovered that not only did I no longer feel compelled to choose between my Jewishness and my acceptance of my LGBTQ+ children, but punkt fakhert, as the Yiddish saying goes—quite the opposite was true. It was the core Jewish values I had carried over from my youth, and perhaps the collective Jewish consciousness of being a permanent “other” across human history, that informed and fueled my advocacy.

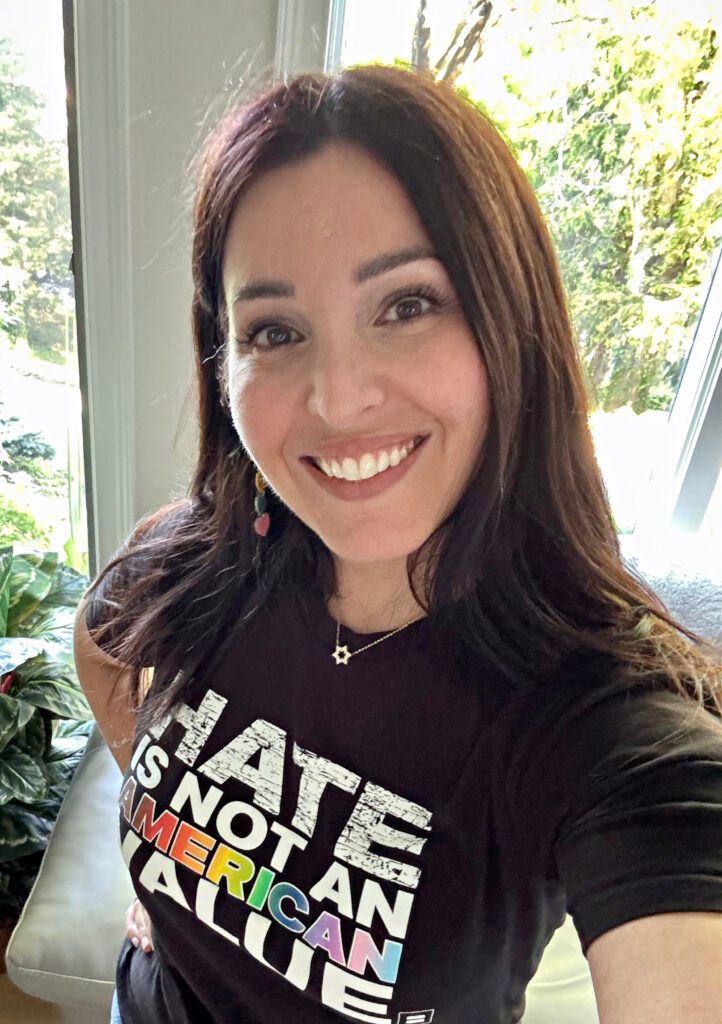

Mimi Lemay advocating for the passage of a non-discrimination bill in 2016 (Photo courtesy Mimi Lemay)

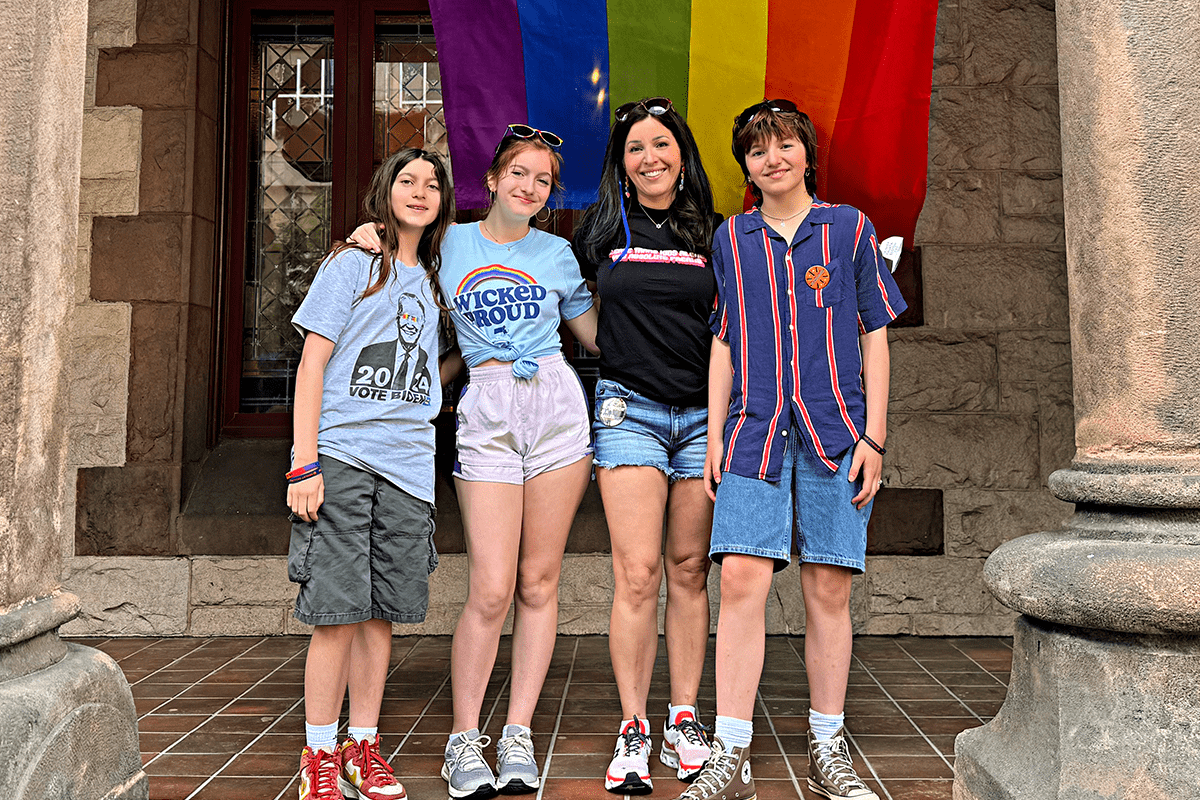

Mimi Lemay’s kids marching in Boston Pride 2017 (Photo courtesy Mimi Lemay)

By the time the pandemic broke in 2020, I was engaging regularly with Jewish audiences from international to local organizations, large institutions like Hadassah and community synagogues and JCCs across the U.S. It was as the “Jewish era” of my advocacy was growing that I began to notice the absence of targeted messaging and support to Jews from what I considered my “home base”—large, national civil rights organizations. I began to suggest ways we could fill in these gaps and build these bridges. The tepid responses I received were disappointing, but I also realized that, in the here and now, American Jews did not experience the acute levels of systemic discrimination that other groups did. I counseled myself to have patience. There were bigger “fires” to put out (the triaging rubric under which we operated was: “Whose house is currently on fire?”). These were the days of the George Floyd murder and protests and the growing national outcry against the systemic inequalities and exponential violence under which people of color labored. Barreling toward us were the disastrous repeal of Roe v. Wade, multiple threats to voting rights, as well as an explosion of attacks on trans youth in Republican-controlled state legislatures. So many fires, so little time.

It was only in 2022 that my two worlds, that of my Jewishness and my progressive activism, became distinctly uncomfortable to occupy in tandem. One such interaction happened at an annual gathering of fellow advocates: A casual remark was made to the effect that a particular person, being Jewish, could not appreciate the burden of discrimination experienced by the speaker.

“A casual remark was made to the effect that a particular person, being Jewish, could not appreciate the burden of discrimination….”

I struggled for a moment in the decision of whether to speak up. I intuited that the remark was not malicious in intent; rather, it came from an absence of understanding of the prevalence and extent of antisemitism, past and present. However, the absence of knowledge itself was problematic. I settled on a gentle reminder that Jews, as a people, have long experienced “othering,” and a Jewish person might well be equipped to empathize with another’s experience of discrimination.

I did not think my remark to be extraordinary or controversial in the least. However, the group moderator swiftly delivered what felt like a rebuke: “It [antisemitism] is not the same!” was said with some force.

I was surprised and dismayed. The unique lived experiences of different historically marginalized communities were typically a welcome conversation in our group. Furthermore, my comment was not comparative in nature. “Of course it’s not the same,” I retorted, flustered, “but it exists.” I listed a few personal examples, as well as those of the wider Jewish community, uncomfortably aware that the “temperature” in the room had dropped. I wondered how my addition of antisemitism as a catalyst for shared empathy could have been taken, prima facie, as reductive of the harm experienced by others. It felt like I had clumsily stumbled into a conversation already in progress, one that I was not privy to and was therefore ill-prepared for. Something had been decided about the Jewish experience that had excluded this experience from all others in the category.

After the session, a few of my fellows continued to try to “educate me,” all well-intended, I assumed, on the disparate natures of different oppressions. One advocate alone seemed to understand my statement. She approached me in a quiet moment. “When you first started talking,” she admitted, “I felt myself go,” here she drew back in a gesture of recoil, “…but then, as you went on, I began to understand. You taught me something new. Thank you for sharing your truth. Keep doing that.” Impulsively, I embraced her, grateful for the acknowledgment that what I had brought into the room was not intended to harm or reduce. It took me hours of mulling over the day’s events to discover the inadvertent clue she had provided for me; a reference to the wider conversation that had excluded Jews, evidenced by her initial recoil at my words.

Since that experience, I have searched for answers across large organizations dedicated to fighting for civil rights, hoping to find evidence that I was mistaken, that antisemitism was included among other forms of hate to be combated. That this subject was not just the purview of the ADL and Jewish organizations. I read books on this subject, from David Nirenberg’s “Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition” to Dara Horn’s “People Love Dead Jews” and comedian David Baddiel’s not-so-funny “Jews Don’t Count.” The shadow conversation I was searching for began to take shape.

I also found allies within these LGBTQ+ advocacy spaces, Jews and non-Jews, eager to begin the conversation about the world’s longest-standing hatred. Measurable change, however, was slow and halting, with many fires springing up around the country.

In the meantime, I continued to straddle my two worlds, my Jewishness and my LGBTQ+ advocacy, carving out spaces where I could do one, or be the other. I joined the board at Keshet, a national LGBTQ+ Jewish organization, and found a place where I could be and do both. Often, I was reminded of my mother’s dilemma: “God gave me two worlds, and I love them both.” I had to find a way, with patience, to cross this divide.

It was then, on an early Saturday morning in October, that my Jewish world caught fire.

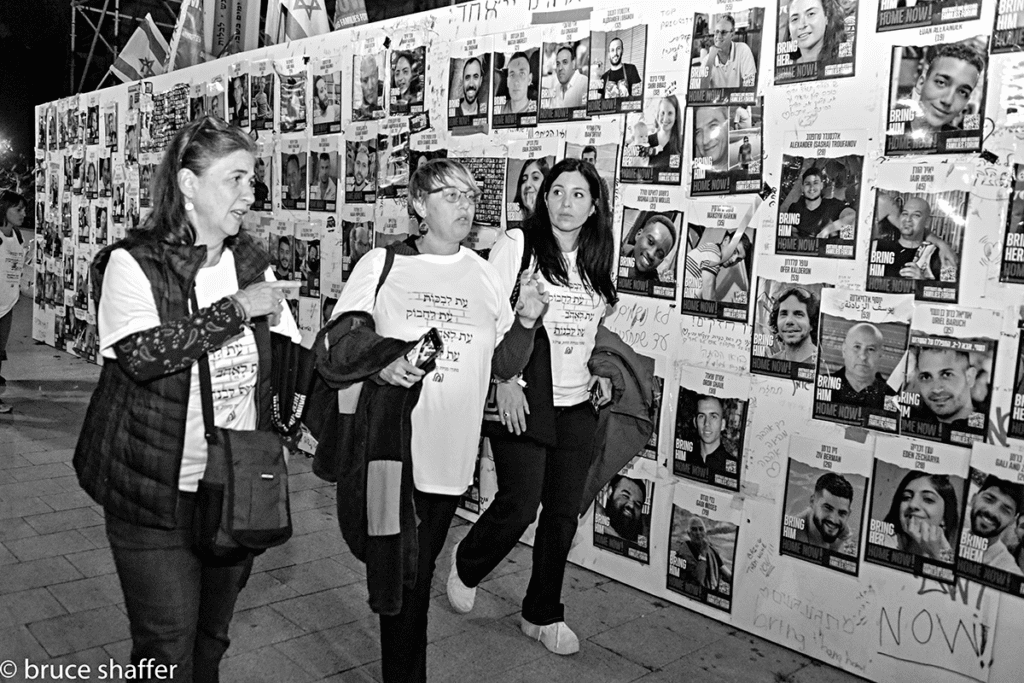

The first weeks after the horrific Oct. 7 passed in a partial haze. Some things, my everyday schedules and interactions, seemed to happen without much deliberate participation on my part. The kids were fed; they made it to school. I kept most of my meetings. I guess I was there? Other moments remain sharp and indelible: The panicky texts and calls to my siblings in Israel, starting with my brother in Jerusalem, father to a toddler with another baby on the way. The moment my sister, who had been in Sinai on vacation, made first contact. The interminable wait until Motzei Shabbat when my religious sister, living in Beitar with her two children, was heard from. The feelings too are indelible: Confusion about what had happened, and what was still happening. The growing horror as confusion turned into certainty, and the numbers of the dead and captured climbed.

These feelings will be familiar to many Diaspora Jews, especially Israeli-born Jews like myself, along with other confounding experiences: The indescribable loneliness of intimate tragedy, while the world outside your window dances by as if nothing has happened. The growing calls, before we had finished burying our dead, for Israel to show restraint in its response. The things that were intimated, or spoken out loud: “What did you expect? Oppression breeds violence.” Later, as the half-hearted or ambivalent acknowledgements turned into vociferous accusations, searching acquaintances’ social media posts for incriminating evidence from that black day. Did anyone cheer for the monsters? Fleeting days of newscasters’ empathy—familiar, formerly comforting faces—now cold and condemning. All the while, the profound ache for the innocent: the massacred dead, the terrified hostages, the Gazans being used as pawns and human shields in a game of their leaders’ devising.

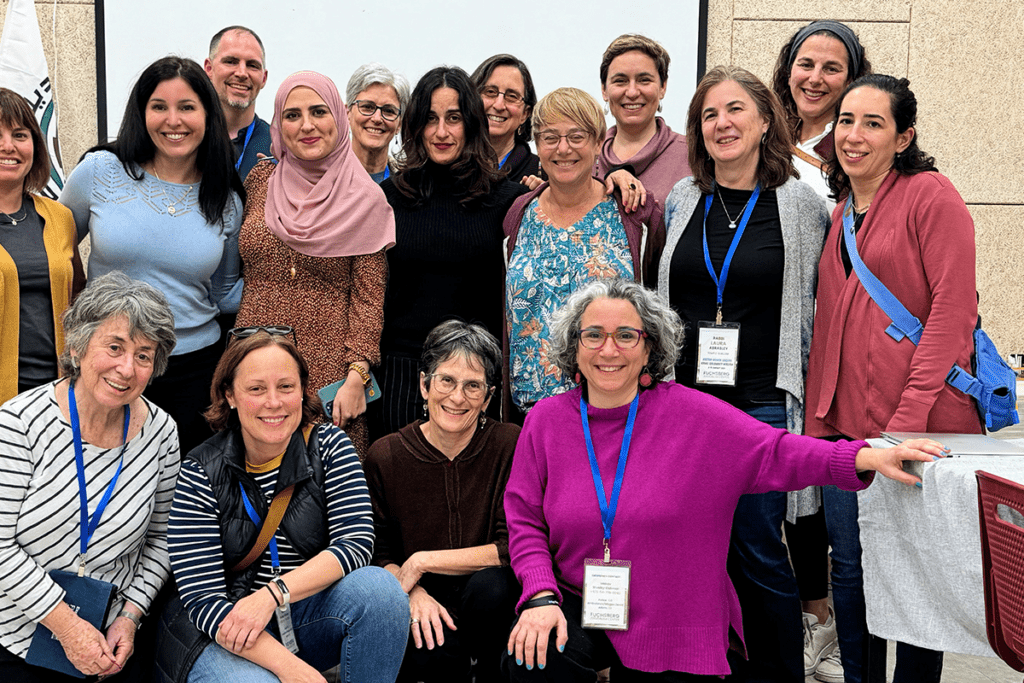

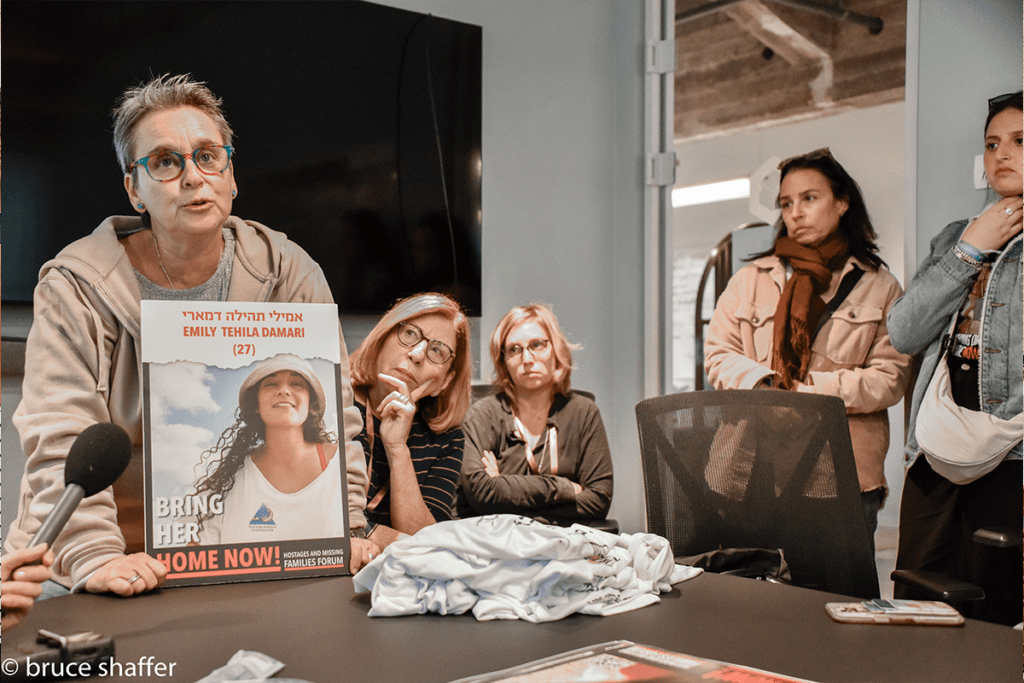

As 2023 came to a close, I could no longer linger in this liminal space. I jumped at the chance to join a Boston Jewish women’s mission to Israel, my feelings for the land and my people no longer complicated by my past. Such is the warped blessing of catastrophe; it brings instant clarification and realignment. In Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, Jaffa and Rahat, our little group met with our Israeli counterparts, human rights activists, civil society entrepreneurs and peacemakers; Jewish, Palestinian and Bedouin. These impassioned women clearly knew the stakes. They knew, and had known for a while, that Israel’s survival as a pluralistic, ethnic democracy hinged on the twin prongs of secure borders and secure human rights, an end to occupation and an end to terrorism. I departed Israel carrying with me precious words of hope spoken by Sally Abed, a Palestinian-Israeli peace activist and leader in the organization Standing Together: “It is often in the darkest times that come the clearest visions.”

On my return to America, I was once again bombarded with voices calling for an expansion of the conflict: “Globalize the intifada!” I realized that, over here, voices of change like that of Sally Abed have been drowned out by the cacophony of crowds. Over here in the Diaspora, some vicious and ancient force was metastasizing. It was my Tel Aviv sister who told me that after Oct. 7, many peacenikim were met with the taunt: “Hitpakachtem?” Have you sobered up? I think about my own recent sobriety on the subject of antisemitism. What were its implications for my advocacy? I have found no satisfying answers yet.

The two worlds I am straddling continue to sap from my spirit in my attempts to reconcile them. There are few places left where I can fully be both a passionate Zionist Jew and a mother who passionately advocates for LGBTQ+ rights. I am also deeply aware that the rift I experience is nothing compared to that which LGBTQ+ Jews themselves are enduring. It seems that they have been presented with an impossible choice: Be the “right kind of Jew” and reject the “white colonialist Zionist oppressor” or the “wrong kind of Jew” whose heart is bound to the survival of the only Jewish state. Jews are familiar with this Damoclean sword, and there is no path that comes without heavy loss. I think of the words of a friend and fellow Jewish advocate: “For the first time in my life, I feel more Jewish than gay.” I hear words of abandonment all around me.

Pride Month has found me, this year, heavy in thought and mired in complexity. I am thinking of all the celebrations to which queer Jews cannot give themselves fully, if at all. I am thinking of the spaces that no longer feel welcoming to LGBTQ+ Jews of color, who, it seems, with a swipe of poster board paint, have been blotted from the narrative of Jewish history. If I am drained in the effort, how do these Jews who live at the crossroads of multiple “otherings” experience this moment?

I still believe deeply in the mission I set out to do nearly a decade ago when I began to advocate for LGBTQ+ equality, and I believe the progressive movement can correct its misconceptions and biases regarding Jews and the Land of Israel. I also believe that the wider Jewish experience is founded on tenets that fully align with LGBTQ+ equality, and that Jews must remain in these and other fights. As a Jewish mother, I cannot abandon either pursuit. I live with a foot in two worlds. And I love them both.

Mimi Lemay is an author and advocate for LGBTQ+ rights. Since 2015, Mimi and her family have fought for passage of equal protections for transgender individuals in Massachusetts and across the U.S., appearing on television and print media with their message of inclusion. In 2017, Mimi joined the Parents for Transgender Equality National Council at Human Rights Campaign, where she remains an alumnus member. In 2019, her critically acclaimed memoir was released: “What We Will Become: A Mother, A Son and A Journey of Transformation,” and was recognized as a 2020 Massachusetts Book Awards finalist. Also in 2020, Mimi was named a Commonwealth Heroine, an award granted by the Massachusetts Commission on the Status of Women. In 2023, after several years of advocating on behalf of LGBTQ+ equality in the Jewish community, Mimi joined the board of Keshet, a national Jewish LGBTQ+ advocacy organization. She also volunteers with the Anti-Defamation League in Massachusetts. Mimi received a master’s in law and diplomacy from the Fletcher School at Tufts University in 2004 and an undergraduate degree in Iran and U.S. foreign policy from Boston University in 2002. She was born in Jerusalem in 1976 and emigrated to the U.S. as a young girl. She now lives on the North Shore of Massachusetts with her three children and a quirky puppy, Penny. Her three siblings all live in the Holy Land with their families.